I recently watched Stanford’s CS229 talk on “Building LLMs,” took some running notes, and put together this easy-to-understand blog to help explain how these powerful language models work.

The blog starts here: 👇

Large Language Models (LLMs) are enormous neural networks trained to understand and generate human-like text. In practice, an LLM “learns” language by reading massive amounts of text (often the entire internet!) and learning to predict the next word in a sentence.

This simple training task turns out to give LLMs broad knowledge of grammar, facts, and even reasoning patterns, so they can write coherent essays, answer questions, and carry on conversations.

Why do they matter? Because LLMs power today’s AI revolution – they are the engines behind chatbots like ChatGPT, code assistants, translation tools, and much more. In short, by scaling up the simple task of word prediction, LLMs have gained impressive capabilities, making them both exciting and disruptive in tech, business, science, and society.

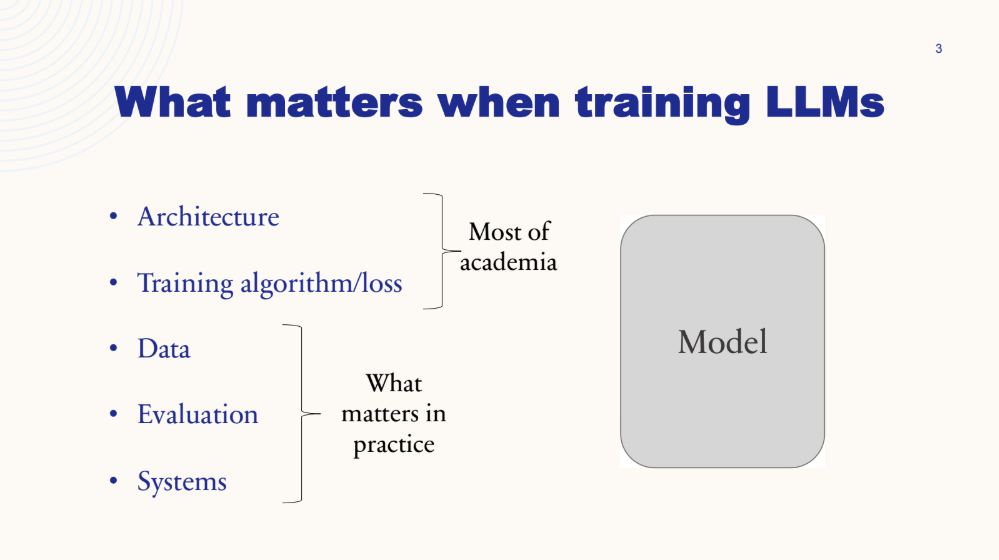

🔑 Key Components of an LLM

Building an LLM involves several key ingredients:

- The architecture of the model

- The training algorithm/loss

- The data it learns from

- How we evaluate it

- The computing systems that run it

Let’s briefly unpack each:

-

Architecture 🔧

→ Modern LLMs almost always use the Transformer architecture. Transformers use layers of “self-attention” to let the model weigh which words in the context are most relevant when predicting the next word. In practice, this means the model processes entire sentences (or long blocks of text) in parallel, rather than one word at a time like older models did.

This architecture was introduced in 2017 (Attention is All You Need) and has proven to be very powerful. In simple terms, a Transformer is a neural network that uses attention mechanisms to connect every new word to the words that came before it. -

Training Algorithm 🎯\ → The classic algorithm is language modeling – given a sequence of tokens (words or subwords), predict the next token. Technically, this is trained via cross-entropy loss (maximize the likelihood of the correct next word), so the model learns a probability distribution over all possible next words. We often report this performance in terms of perplexity, which measures the model’s uncertainty. (Lower perplexity means the model is less “surprised” by the text.) Over the years, LLMs have gotten dramatically better at this: state-of-the-art models today are so confident that their average “hesitation” between word choices (perplexity) has fallen by an order of magnitude compared to just a few years ago. However, perplexity alone doesn’t capture tasks like following instructions, so we also evaluate LLMs on benchmarks.

-

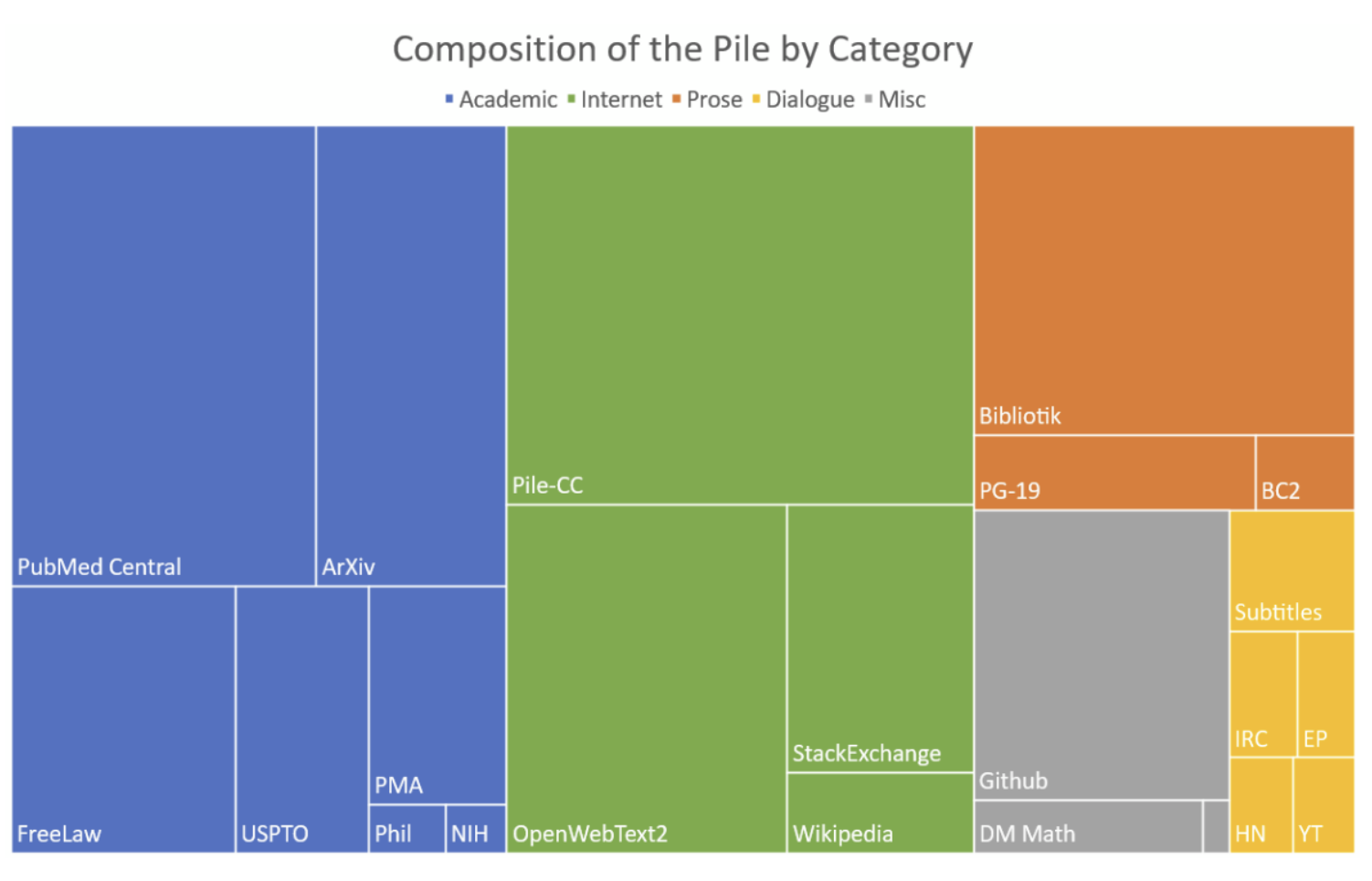

Data 📚\ → LLMs are trained on huge text corpora. A typical pipeline is to start with a web-scale crawl of documents (e.g., Common Crawl), then clean and filter them. This involves steps like stripping HTML to get plain text, removing illegal or harmful content (profanity, personal info, copyrighted material, etc.), and deduplicating repetitive boilerplate. For example, GPT-3’s training data included about 410 billion tokens from a filtered Common Crawl (over half its dataset) plus curated sources like WebText and books. After initial filtering, data scientists often apply heuristics or models to throw out low-quality text (very short pages, gibberish, spam), and they might mix domains deliberately (like weighting scientific text, code, or dialogue) to improve performance on specific tasks.

In short, what an LLM learns is heavily determined by the data it sees: gathering and curating high-quality, diverse data is a huge engineering effort and one of the main factors in an LLM’s success. -

Evaluation ✅\ → We need ways to measure how well the LLM is doing. During training, we might watch the validation loss or perplexity to ensure it’s learning. But for real-world performance, we use benchmarks. There are many multi-task benchmarks (e.g. MMLU) that test general knowledge, reasoning, language comprehension, and more. On these tests, the LLM must predict correct answers or generate text that matches a “gold” reference. In practice, LLMs are often put through standardized NLP tasks (from language understanding to math or coding tasks), and their success rates are reported.

(For example, GPT-3’s creators reported it achieved ~44% accuracy on the MMLU benchmark, which was impressive at the time.) New leaderboards and “holistic” benchmarks (like HELM) aggregate dozens of tasks so we can compare models. Realize, however, that such benchmarks are only proxies; they can miss how helpful or safe a model is in real conversation. Human evaluation (asking people to rate the outputs) is also used, especially for aligned chatbots. -

Systems/Infrastructure 🖥️\ → Training and running LLMs require huge compute resources. Training a state-of-the-art model can take thousands of GPUs working in parallel for weeks. For example, one recent 400 B-parameter model (LLaMA 3) required on the order of 16,000 Nvidia H100 GPUs running for ~70 days – roughly $70–80 million worth of compute!. To make this tractable, engineers use techniques like mixed-precision arithmetic (storing numbers in 16-bit instead of 32-bit to speed up matrix math). They also use parallel training across a cluster of machines: data parallelism (each GPU gets a slice of each batch and they sync gradients) and model parallelism (the model’s parameters are split across GPUs). Libraries like DeepSpeed or Megatron and hardware interconnects (NVLink/InfiniBand) are key. Inference (using the model) also uses GPU clusters and optimizations to handle the massive model size.

In short, LLMs push current hardware to the limit, and making them efficient, from careful GPU utilization to pipeline parallelism, is an entire field of its own.

🔁 Pre-training vs. ✍️ Fine-tuning (GPT-3 vs. ChatGPT)

→ An important distinction is between pretraining and post-training (fine-tuning). Pretraining is what we described above: unsupervised language modeling over broad data. GPT-3, for example, was essentially a pure pretraining model (it learned from text only, with no extra instruction tuning). But such models don’t necessarily do well when aligned to user instructions. In fact, OpenAI’s team notes that because GPT-3 was only trained to predict the next words, it could produce answers that are grammatically plausible but not what a user really wants.

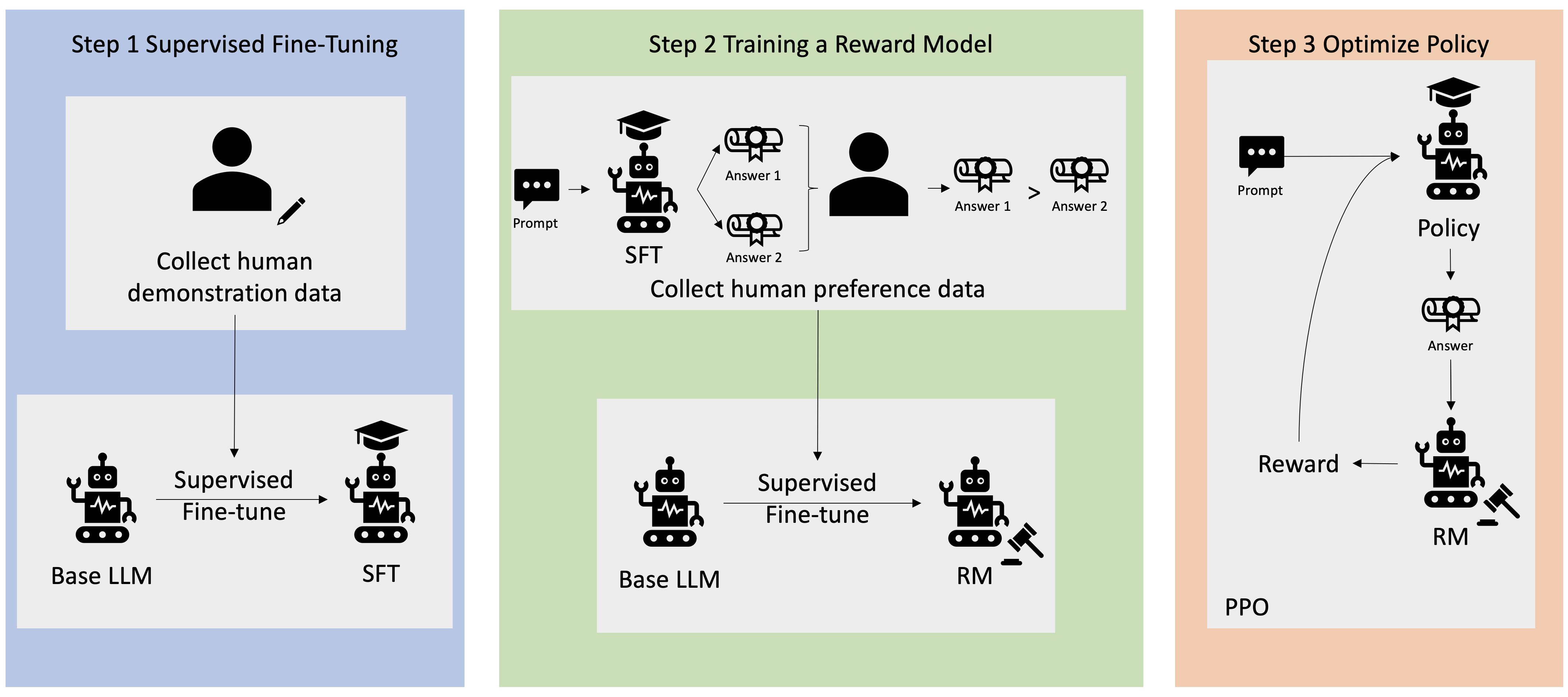

Post-training (sometimes called “fine-tuning” or “alignment training”) adds a supervised step. First, one collects a small set of instruction-response demonstrations written by humans (for example: “Explain X” and a good answer). The LLM is then fine-tuned on this data, using the same next-token objective but now focusing on the style of those answers. This step is known as Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT). In practice, only a few thousand examples are often enough to teach the model the desired format or tone, because the knowledge is already in the pretrained model – SFT just “shapes” it. The GPT-family extended this idea: for example, InstructGPT (which underlies ChatGPT) was GPT-3 after SFT on demonstration data of good answers.

The final boost comes from Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF). Here, the goal is to directly optimize for human preferences rather than likelihood. In an RLHF pipeline, the model first generates multiple candidate answers to a user instruction. Human labelers then rank which answers they prefer. This data trains a reward model that predicts “how much humans will like this answer.” Finally, the LLM is updated (using policy optimization) to produce answers that maximize this reward. In effect, this fine-tunes the model to be helpful, truthful, and safe. For example, OpenAI’s team reports that humans preferred the outputs of their fine-tuned model over the raw GPT-3 answers by a wide margin. The model we know as ChatGPT went through these steps: pretrained language modeling + supervised fine-tuning + RLHF. That’s why ChatGPT feels much more on-point and “aligned” to questions than the original GPT-3 (even though it may be smaller in size).

That’s how ChatGPT was born: GPT-3 → SFT → RLHF.

📦 Data: Sourcing, Filtering, and Curation

→ As noted, "Data is King" for LLMs. Teams typically start by downloading enormous web crawls (e.g., hundreds of billions of web pages). For instance, Common Crawl – a freely available web archive – has on the order of 250 billion web pages (many petabytes of data). After the extraction of text, the raw data is incredibly messy. To get a high-quality training set, engineers apply multiple filters: removing outright garbage, stripping pages with too many coding fragments or markup, filtering out pornography or hate speech, and deleting personal information. They also de-duplicate at various levels: removing duplicate pages, duplicate paragraphs, etc., since repeating the same text over and over would waste training and bias the model.

There are even model-based filters : for example, running a smaller classifier or language model to flag pages that look low-quality or off-topic. After cleaning, the text is often split into categories (like web text, books, code, dialogue) and then mixed carefully during training so the model sees a balanced diet. (Some research uses scaling laws to decide how much of each domain to use for best performance.) The outcome: a curated dataset of high-quality tokens for pretraining. Many of the exact recipes are secret, but common open sources include C4 (around 150B tokens), The Pile (280B tokens of mixed English text), and others that researchers share.

In short, LLM data engineering is far more than “just scraping the web.” It’s an art and science of filtering and curating billions of words so that the model learns from good examples. The choice of data greatly affects what the LLM “knows” and how it behaves.

📈 Why “Scaling Laws” Matter?

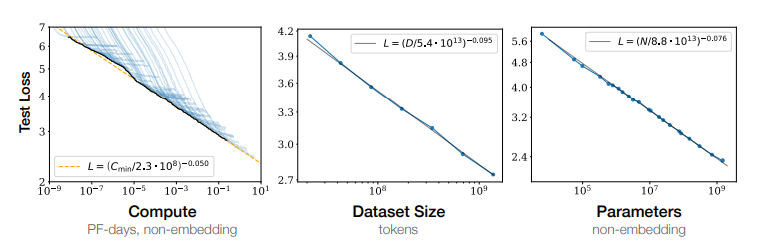

→ A key discovery in LLM research is that bigger is (almost always) better – and in a predictable way. Early studies (Kaplan et al., 2020) found that as you increase model size, dataset size, and compute, the model’s loss improves smoothly according to power laws. In practical terms, this means that training a model with 10× more parameters or using 10× more data will generally make it measurably better (though with diminishing returns). Crucially, these scaling laws allow researchers to plan ahead : given a budget of compute, one can solve for the optimal number of model parameters vs. training tokens. For example, follow-up work (the “Chinchilla” scaling laws) showed that to use compute efficiently, you often need to train somewhat smaller models on more data, challenging the intuition “bigger is always better”.

Why is this important? Because LLMs are so expensive to train, we want to make sure we’re not wasting resources. Scaling laws tell us how to trade off bigger models vs. longer training vs. more data. They also reinforce the “ bitter lesson ” in ML: given enough data and compute, even simple architectures scaled up can outperform more complex ideas.

(In fact, a famous quote is: “The only thing that matters in the long run is the leveraging of computation.”) Real-world training budgets are huge – on the order of $10M–$100M – so following these laws helps tech teams use that money wisely. Ultimately, scaling laws set expectations: they tell us that future LLMs will get better as compute grows, but also highlight that gains will slow down if data or compute run out.

🎛️ Aligning LLMs to Human Preferences

→ As hinted above, raw language models can be capricious. Alignment techniques ensure they follow human intent. We already discussed supervised fine-tuning (SFT) on human-written answers – this teaches the model to imitate helpful answers rather than random Internet text. RLHF goes further by actually using human feedback. In practice, after SFT, the model generates multiple candidate answers to an instruction, and human raters pick which answer they like best. This preference data trains a reward model (essentially, a learned “happiness function”). Then the model is updated via reinforcement learning (e.g., PPO) to maximize this reward, meaning it will produce outputs that humans have judged to be good.

The result is dramatic. For example, OpenAI reported that their labelers strongly preferred outputs from the fine-tuned InstructGPT model over the raw GPT-3 outputs, even though InstructGPT had only 1.3B parameters versus GPT-3’s 175 B. This shows that alignment can more than make up for size: a smaller model guided by human preferences can outshine a much larger unguided one. In summary, alignment (via SFT and RLHF) is what makes an LLM turn into a helpful assistant rather than a random sentence generator.

⚙️ System-Level Challenges: Compute and Optimization

→ Finally, it’s worth appreciating the system engineering behind LLMs. Just to train these models, organizations build enormous clusters of GPUs. Each step of training involves huge matrix multiplications (tens of petaflops!), and data must flow rapidly between machines. There’s intensive work to reduce overhead: using mixed-precision (e.g., bfloat16 arithmetic) to double throughput, fusing operations to minimize slow memory access, and carefully scheduling data movement. Frameworks like NVIDIA’s Tensor Parallelism or Microsoft’s ZeRO enable splitting a model’s weights and computation across many GPUs so that a single batch can be processed in parallel.

The power requirements are also staggering. As mentioned, training a 400 B-parameter model can emit thousands of tons of CO₂ and cost tens of millions of dollars. Even inference (serving an LLM to users) requires optimization: companies use smaller distilled versions or offload parts of computation to CPUs or less-frequent custom chips to save energy and time.

In short, building an LLM isn’t just writing some code – it’s running a small supercomputer. Innovations in hardware, compilers, and distributed systems all play a big role in making LLMs feasible. As one author notes, distributing training efficiently (deciding how GPUs should communicate and sync) is one of the “ultimate challenges” in machine learning today.

🔮 The Future of LLMs

→ Where is the field going next? Most researchers agree that scale will continue to matter: we’ll see ever-larger models and more data (until we hit a “data wall” of all available text). But there are also new directions. Multimodal LLMs (models that handle images, audio, code, etc., in addition to text) are already emerging – GPT-4 is a text+image model, for example. We’ll likely see sparsity and mixture-of-experts designs (models that activate only parts of their massive parameter set per task) to reduce compute cost. Context windows (the amount of text the model can “see”) keep growing; researchers are working on extending these to handle entire books or real-time data streams.

Alignment and safety will be even more crucial. Work on avoiding bias, preventing misuse (disinformation, hacking, etc.), and complying with laws around data use is ramping up. We can also expect more out-of-the-box integration: LLMs wrapped into apps and tools (like how ChatGPT is now an API for building products). In the next few years, a friendly AI assistant that can chat, draw, write code, tutor students, and more seems quite plausible, as long as we continue investing in good data, clever training, and keeping these models aligned with human values.

For further learning, Stanford’s CS229 guest lecture on “Building LLMs” offers an in-depth look at the architecture, data, training, and systems behind large language models. As the field rapidly evolves, mastering concepts like scaling laws and RLHF is key to understanding how LLMs achieve powerful results through massive-scale language prediction and fine-tuned alignment.

📚 Sources:

This blog is inspired by the Stanford CS229 Guest Lecture on Building LLMs.

Access the slides here:

🔗 Stanford CS229 LLM Lecture (Week 8)

Citations: